d thrust a copy – “I know you’ll love this movie and it will be years before your see this if you don’t take it.” He knew I didn’t approve of unofficial copies. My school is in a small village and our two hundred children – like us – are cut off from the rest of the world. I watched the movie in Mumbai with my sister. Then came home and that very evening watched it with my mom and husband. That Saturday I watched it with the teachers in my school. They know no Hindi and so the three hour movie ran to almost 4 with all the explanations.

d thrust a copy – “I know you’ll love this movie and it will be years before your see this if you don’t take it.” He knew I didn’t approve of unofficial copies. My school is in a small village and our two hundred children – like us – are cut off from the rest of the world. I watched the movie in Mumbai with my sister. Then came home and that very evening watched it with my mom and husband. That Saturday I watched it with the teachers in my school. They know no Hindi and so the three hour movie ran to almost 4 with all the explanations.Then I screened it for the teachers of a nearby school; and finally, last evening I screened it for my children in the 6th, 7th and 8th standard. With the children, it meant a class on the last few years of Indian independence movement and the turmoil of partition. I used a pre independence map and the India map today. The demand of Pakistan and Radcliff’s instructions for drawing the boundary that caused untold misery for millions; the conditions of the refugees at the camp in Delhi; the families that uprooted themselves and settled on either side became poorer; and all in the name of ‘security’ and ‘equality’.

There were questions, but one which was relevant to my purpose was: was anyone happy to have come to India?

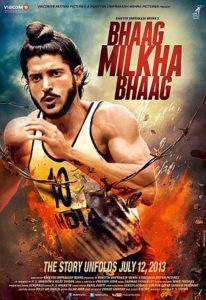

I told them the story of Milkha Singh in brief. I wanted the movie to do its work.

As the movie progressed I stopped and explained. They enjoyed the scenes of the recruits being trained, Prakashraj rolling his eyes, Milkha guzzling the ghee, the lateral use of a cricket ball, the catchy song scenes; suitably horrified by the roughing of Milkha, awed by Milkha training in high altitude, winning all the medals and the final victory against Khalique. The movie ended and a statement was made: but he never won the Olympics, so his life was not fulfilled.

Tomorrow I shall be back in class with a single question.

What was Milkha’s real Olympics?

I have found that while dealing with the growing mind a direct statement is either shunned or completely accepted without personal evaluation of the statement. Either way, it is a dead loss. I have found movies one of the best mediums to discuss, draw and help children find their own answers to whatever questions they might have and are trying to solve. For, in essence, all questions boil down to one single question: how should I find harmony in my circumstance? How can I lead a happy life?

Which was Milkha’s question. How could he find harmony within himself, haunted as he was by the cruelest memory? Death for any child is incomprehensible; wanton killing unbearable. Being a witness to the killing of one’s family a horror. Orphaned and alone, with very little literacy, he travels all the way from Multan to Delhi. The fear, the disbelief, the horror does not permit him to cry. He starts life in India as a child who must learn to fend for himself. But he has a thick layer of protection – a protection that stands good all through his life: the love his family had for him. If Milkha loved something it was to be a cynosure of all eyes. Reciting a hodgepodge rhyme and having the family clap their hands and make much of him is a memory that keeps his heart warm and alive. Even when he takes to theft, small time gambling, the essential character remains: there is good humor and laughter in it all. Even as he ran laughing across the hot desert sand and crossed the Chenab to go to school, so does he go through the desert period of his life: clowning on a cycle while urchins cheer him on; raising Cain with the local constabulary. Anything for a laugh, any way for a simple living, any idea to keep people think he is a hero. Deep down, again and again, he remembers his grandfather’s words, ‘you are born for great things, Milkha.’

An information passed to him casually by his girlfriend that a nation is given a holiday on Gandhiji’s birthday because he was so great, catches his fancy. His dream: to have a holiday declared nationwide because of him. Dreams are deep; dreams are wishes made by the heart and the heart always makes it come true. In that moment, Milkha kick starts his life.

It is always interesting to a student of history, or a philosopher, how Life decides to act to fulfill a dream. Milkha joins the army as a recruit who barely knows to read or write. Two forms of education begin: the physical, where his body is trained to obey his will and formation of an indomitable will and discipline that grows with every challenge. At every moment there are choices opened for him. Dance, sing, drink with the girls or focus on his training. When he decides to refocus, he graciously apologizes to the girl. “Sorry, Sarah. You no problem ji, I problem.” He wins her goodwill and heart all over again and so he is free to concentrate on his game.

The Pakistani coach sneers at him. “Well, you ran from Pakistan and have been running ever since.” Sometimes our enemies are our best friends. The words inspire Milkha to run like he had never run before and win. Milkha wins the Asian Games, Commonwealth Games in Cardiff; he is presented his gold medal by Queen Elizabeth and he meets the Duke too. For the nation it is a moment of pride. For Milkha, who is still fighting his horrific past, it is a pause. A boy with hodge podge rhyme, a man who could not string a real sentence, by now speaks English, has learnt to write too.

Interesting: literacy comes from education not the other way around. A great pedagogical Truth. What every philosopher and educationist the world over repeats but no school pays attention to: learning of the alphabets or reading should come as a consequence to an abiding interest created by a teacher / adult; from the insatiable curiosity that is nurtured the young child should want to read and know for himself. Personally, it was a lovely moment.

And with education comes dignity and grace. India is invited by Pakistan to friendly games and Pandit Nehru declares Milkha Singh will lead the contingent. Milkha refuses. Nehru sends his two coaches and the sports minister to meet Milkha at Chandigarh. They have no idea what to say to him and so talk about the weather, the plants in his house, the tea. Milkha says, “I am sure you have not come all this way to discuss the weather or the tea. Tell me.”

“Panditji would like to meet you!”

The meeting is very simple and short: Milkha makes his feelings known but Panditji overrides him. He is a soldier and there are battles that are not always fought on battle fields. Milkha is mature enough to understand: his personal hate of Pakistan is up and he must confront it. Life was sending him back to where all his tribulations began. Was there a reason?

He revisits his home. For the first time he cries and thus the catharsis. His childhood friend has now occupied his home. His home that he thought he had lost he sees is revered by his friend. His friend’s wife offers Milkha’s favourite drink: milk. It was a homecoming that he did not expect. His home was loved. Milkha grows once more: he sees his love for his family and home come back to care for him again.

At the games, Milkha wins. General Ayub Khan bestows on him the title “Flying Sikh,” and says that all of Pakistan is honoured to have him there. Milkha smiles.

What about the dream? That which the heart makes? When Panditji said, “Tell me Milkha, if you win the match what would like me to do for you?” Milkha says, “I would be happy if you declared one day’s holiday for all of India.”

For what is in the deepest of heart comes easily to the lips. Milkha’s reply stems from a sense of equality that comes from valuing oneself. Education as it should be.

So, then, what am I going to tell my children tomorrow?

That Milkha’s Olympics was not in the races he ran or won or lost. His Olympics was with himself: to reconcile, to know that Life had always cared for him even when he was hungry and sitting on a shroud; to learn to love again even as his friend had kept him in his memories; that the Spirit was his and his alone. That Milkha had choices to make every day: every time he chose wisely, the river of Life flowed.

That to have a dream is important and to make it broad and as all-encompassing as possible. If you dream of caring for people and learn well, Life will make outstanding teachers, doctors, nurses, academics or enlightened managers of you. Life would consider your inherent qualities, your potential and lead you to the right place, at the right time. That it would be fun to flow with what Life will deal and discover its meaning. But dreaming of ‘becoming’ a teacher, a doctor or a software engineer is limiting Life’s possibilities. For then, when you have ‘qualified’ the stalemate will begin and you will repeat yourself ad nauseam.

So dream. Dream large and nice. A dream that will set you on an adventure. A dream that ‘ Life [will] want to take them and make them a Man’. A dream that you will spend an entire life time perfecting.

The movie isn’t about Milkha at all. It is about you. For in the Oneness of Being you are all also Milkha.

That is what I will tell my children tomorrow. I am not going to tell them what to dream. I am going to tell them how to dream.

As written for and published in Parent Cricle megazine.

~Aruna Raghavan