A world-class school for the underprivileged in Tamil Nadu

A world-class school for the underprivileged? It’s possible, says Ahana Advani, who visited such an institution in Tamil Nadu.

In every other respect, Arasavanangkadu, 400 kms from Chennai, Tamil Nadu, is just another remote village in India: frequent power cuts, and not even a simple kirana store. Yet, in the midst of its 350 homes – the majority, thatched huts – and its population of 2,000 people – mainly poor, illiterate farmers – there exists an extraordinary, world-class institution.

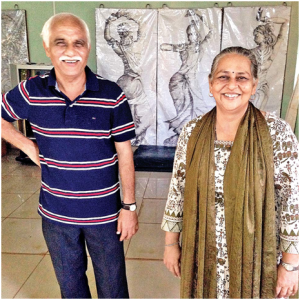

Twenty-one years ago, an inspiring couple, Aruna and Raghavan, at age 31, left Mumbai life to settle in this village. Passionate teachers, both had spent 10 years at various schools, including the Kodaikanal International School. Raghavan, a software engineer and chartered accountant and Aruna, an MPhil in English, chose instead to open a free school for needy children.

Since 1994, their Shikshayatan Middle School, a Tamil medium institution, has empowered its students with proficiency in English, their doorway to the world. From 20 students in the Raghavans’ home, it now gives an education, uniforms, textbooks and snacks to 225 students, on a four-acre, green campus, without charging a single rupee. It uses computers in everyday teaching, and in its science and language laboratories. Aruna says, “We must provide free education to the underprivileged. A child who is educated will never need doles in the future.”

The reason for Shikshayatan’s success is its innovative teaching method. Aruna and Raghavan have integrated the insights of Shri Aurobindo and the Mother, 20th century Indian philosophers, with the flashcard method used at Glenn Doman’s Institutes of Achievement of Human Potential, USA.

The students go up to the eighth grade without the stress of homework or exams. As a result, they are eager to learn, with amazing results. More than 70% who go on to join government schools score greater than 80% in their high school diplomas. One student got 96%.

Shikshayatan alumni have become engineers and teachers, usually through grants from the school. One is a dentist, another, a Bharata Natyam dancer, and still another, a budding chef. “If there are not more,” says Aruna, “it’s because girls are not yet encouraged to pursue such studies, and the parents’ finances do not stretch to include expensive courses.”

“I wanted to find the right way to teach, before my qualification, and I found that here,” says Kirsty Minton, from Cambridge, England, teaching English at the school for a year. Like her, there have been many volunteers: Fiona Farley, a historian; Susie Goldring, a BBC producer, among others. Raghavan reveals, “We routinely have volunteers from UK, Germany, USA, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and UAE. Hence our children get exposed to German, Spanish and French, other than English, though we are a Tamil medium school.”

Such diversity renders these village children far more knowledgeable than many of their urban peers. In fact, Nirupama Raghavan, the founders’ daughter, schooled at Shikshayatan, is pursuing undergraduate studies in Canada.

I volunteered at Shikshayatan in June 2014 and taught Science and Mathematics. A high point of my visit was taking the mobile science lab to the local government schools, with an outreach of 2500 students. Here, Mr. Vetri, the science teacher and I demonstrated interactive science experiments.

I observed that boys are encouraged to participate, but the girls remain silent. In contrast, Shikshayatan kids, regardless of gender, express their curiosity freely, without fear of failure. Mr. Vetri explained, “Shikshayatan is a place which creates opportunities for teachers and students to identify their abilities.”

The school’s 25 teachers have a stake in its success, as they are drawn from the village itself. They get their B.Ed through distance learning, usually on a grant from the school. But it is the extensive teachers’ training workshops under Aruna and Raghavan that shapes their vision.

In one session, I took my students on an imaginary tour of London, displaying iconic buildings like the Tate Modern and the Shard. To my delight, the students drew interesting parallels with the neighbouring Brihadeshwara Temple, a World Heritage monument. When I described Matisse at the Tate, a young boy piped up, “Any Picassos on view?” Six students had been to Scotland in 2009, to display their art in the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. It was the first time they had left their village, and travelled on an airplane.

As Shikshayatan turns 20 on August 15, 2014, the Raghavans too dream of soaring higher: expanding to the 12th grade, even establishing a Teachers’ Training Academy. Meanwhile, their low-cost model of holistic learning has helped 50 schools in Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Malaysia, and is growing. Earnings from school consultancies and other donors keep Shikshayatan funded, but there’s much to be done. Its pedagogy, with equal emphasis on academics, creativity and sports, also works well on children with learning disabilities – “differently enabled,” as the Raghavans call them.

Govindaraj, the son of a bakery worker, and a recent alumnus of Shikshayatan, has just been admitted to the DJ Academy of Design in Coimbatore, winning a seat on merit, for which over 10,000 applicants competed. He says, “I owe everything to Shikshayatan. It’s given me not only an education, but a life.”